Philosophical Despair

Periodically I go through a sort of crisis point in my thinking where everything I've been working on suddenly seems to fall apart, where I lose the thread of where I'm going, and suddenly I experience myself as detached from all that I'm doing. The activity of philosophy comes to seem ridiculous to me, like a kind of madness that I've been suffering from, and I come to wonder why I bother at all. Everything comes to seem futile and I find myself bewildered, not knowing how to get through this maze. Decisions I had made just weeks ago so confidently come to look like the wrong decisions, like the wrong paths, and I have to start all over again after a period of quasi-convelescence and detached depression, where nothing in the world excites me any longer or captures my attention. I suspect that there are probably psychoanalytic reasons for this, that this vascillation has little or nothing to do with philosophy, but are instead the result of some other guilt or crime, of some betrayal of my desire, or to some desire I haven't faced movitating my own philosophical wanderings and which call for the abandonment of my work, lest I get too close to satisfying that desire.

Periodically I go through a sort of crisis point in my thinking where everything I've been working on suddenly seems to fall apart, where I lose the thread of where I'm going, and suddenly I experience myself as detached from all that I'm doing. The activity of philosophy comes to seem ridiculous to me, like a kind of madness that I've been suffering from, and I come to wonder why I bother at all. Everything comes to seem futile and I find myself bewildered, not knowing how to get through this maze. Decisions I had made just weeks ago so confidently come to look like the wrong decisions, like the wrong paths, and I have to start all over again after a period of quasi-convelescence and detached depression, where nothing in the world excites me any longer or captures my attention. I suspect that there are probably psychoanalytic reasons for this, that this vascillation has little or nothing to do with philosophy, but are instead the result of some other guilt or crime, of some betrayal of my desire, or to some desire I haven't faced movitating my own philosophical wanderings and which call for the abandonment of my work, lest I get too close to satisfying that desire.But on a less psychoanalytic note, I wonder if these vascillations don't also have to do with transformations in philosophy itself. There's a curious split between my classroom teaching and the philosophical positions I endorse in writing. In the classroom I am a champion of the rationalist trad

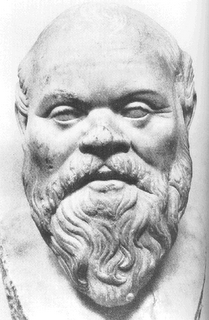

ition, teaching Plato, Descartes, Leibniz, Kant and so on. I can barely stand to teach Hume, Mill, or Nietzsche (or any empirically minded thinker for that matter), despite having a great love for both Hume and Nietzsche (while feeling antipathy towards Mill). I emphasize foundationalism, the search for a ground, reason, sound argumentation, overcoming appearances, the transcendence of standards such as the Platonic forms. I delight in the twists and turns of Socratic dialogue, carefully mapping out the moves Socrates makes in a dialogue like the Euthyphro, where he progressively detaches the question of piety from any sort of mythological grounding (his rejection of the stories about the God's as adequate for telling us what piety is), any grounding in the brute will of the authority premised on the tautology that "the law is the law" (whether that authority be from priests or from the will of the Gods themselves; Socrates emphasizes that if piety is piety then it is piety independent of the will of the Gods, i.e., they love it because it's pious, it's not pious because they love it), thereby allowing us to raise questions of virtue, justice, and the Good independent of any talk of divine will or revelation. I teach the allegory of the cave as a critique of ideology, emphasizing the manner in which the prison-guards, the true sophists, are the ones carrying the cut-outs that cast the shadows on the wall. I teach them how to construct essential definitions, emphasizing how action is premised on knowledge, and how definitions that are too narrow can lead to disaster (such as the Nazis defining "human" as "Aryan") and how definitions that are too broad can lead to absurdity (such as defining "human" as creatures that have opposable thumbs leads us to include racoons under the category of human, thereby leading us to prosecute racoons for trespassing and theft when stealing our garbage, and leading to the bitterly debated "Racoon-Marriage Issue"). I suppose Socrates is one of my heros, even if I'm terrible at "being Socratic".

ition, teaching Plato, Descartes, Leibniz, Kant and so on. I can barely stand to teach Hume, Mill, or Nietzsche (or any empirically minded thinker for that matter), despite having a great love for both Hume and Nietzsche (while feeling antipathy towards Mill). I emphasize foundationalism, the search for a ground, reason, sound argumentation, overcoming appearances, the transcendence of standards such as the Platonic forms. I delight in the twists and turns of Socratic dialogue, carefully mapping out the moves Socrates makes in a dialogue like the Euthyphro, where he progressively detaches the question of piety from any sort of mythological grounding (his rejection of the stories about the God's as adequate for telling us what piety is), any grounding in the brute will of the authority premised on the tautology that "the law is the law" (whether that authority be from priests or from the will of the Gods themselves; Socrates emphasizes that if piety is piety then it is piety independent of the will of the Gods, i.e., they love it because it's pious, it's not pious because they love it), thereby allowing us to raise questions of virtue, justice, and the Good independent of any talk of divine will or revelation. I teach the allegory of the cave as a critique of ideology, emphasizing the manner in which the prison-guards, the true sophists, are the ones carrying the cut-outs that cast the shadows on the wall. I teach them how to construct essential definitions, emphasizing how action is premised on knowledge, and how definitions that are too narrow can lead to disaster (such as the Nazis defining "human" as "Aryan") and how definitions that are too broad can lead to absurdity (such as defining "human" as creatures that have opposable thumbs leads us to include racoons under the category of human, thereby leading us to prosecute racoons for trespassing and theft when stealing our garbage, and leading to the bitterly debated "Racoon-Marriage Issue"). I suppose Socrates is one of my heros, even if I'm terrible at "being Socratic".Daily I sing hymns to mathematics (the only thing I've ever really believed in anyway), songs of the transcendence of mathematical objects and truths, to the fact that they aren't merely human constructs or abstractions, and how mathematical truths are discovered not invented (though I'm not so sure I believe this). And I do all this because I have the belief that my students believe (my transference to my students) that everything is a matter of perception, subjectivity, personal opinion, or that there are no transcendent truths. In short, I act the part of the sophist, defending the thesis that there are rational truths, truths not discovered through sensation and experience, but discovered through reasons and that these truths are true independent of human minds, leading to the possibility that one might be mistaken by what they believe to be true. That is, premised on a reigning ideology of perspectivism, that all is interpretation, one perspective being as good as another, there is no reason to question one's own perspective as there is no ultimate truth to be found. In this regard, the possibility that there is truth is far more traumatic than the possibility that all is interpretation, as it holds out the possibility that one might be in error. I therefore adopt the stance of the rationalist because I believe a teaching that follows the lines of a Hume (all is custom) or a Nietzsche (all is perspective/interpretation), already plays into their ideology and, in no way, serves to awake them from their dogmatic slumber. Of course, I do all this with a great deal of humor as well.

Yet in my written philo

sophical practice, I am an anti-foundationalist, believing that there is no ultimate ground, that there is no secure foundation for [representational] truth, and emphasizing the emergence of universes of reference (of course, I make exceptions for the Lacanian real, truth in Badiou's sense, and mathematics). There is thus a great schizophrenia between my teaching and my writing. And indeed, it could be asked, whether my teaching isn't really my truth or my genuine conviction. As Zizek argues, the symbolic isn't premised on my personal belief in it, but rather, the efficacy of the symbolic is premised on my belief that others believe in it. I don't mow my lawn because I believe it's important to mow my lawn, but rather I mow my lawn because I believe my neighbors believe that it is important to mow the lawn. Thus, if I am a defender of reason, forms, foundations, grounds, and truths in the classroom, understanding my own practice as that of being a sophist in relation to my students so as to awaken them from their relativistic slumbers and critically think through these things, isn't this conception of myself as a sophist cynically propogating the myth that there is rational truth itself just a fantasy that allows me to avoid confronting the traumatic truth about myself, that it is I who really believes these things or hold these convictions? Isn't this the trauma that I experienced in the United States after 9-11 as I watched the nation so easily succumb to the most elementary ideological tricks described by George Orwell in 1984, believing that this was impossible after the WWII era, yet seeing it unfold right before my eyes, horrified to discover that persuasion and reason somehow do not really work, that we are not rational creatures? Yet my thought process here is muddled. The more accurate thematization of my transference with regard to my students would be that it is I who am the genuine nihilist and relativist, and that in a desparate attempt to deal with the directionlessness of my lack of conviction, I instead project this Nietzscheanism on to them so that I might persuade them, all the while persuading myself, that there is some truth independent of their will, perception, or subjectivity. The old-school Freudians, no doubt, would diagnose this as a megalomaniac fantasy, or the unconscious desire to create the world oneself by possessing sovereign power over the creation of truth. Nietzsche says something not dissimilar in his analysis of the will to power, behind the will to truth, where he points to the way in which the philosopher, in his ressentiment, elides the performative dimension of his discourse.

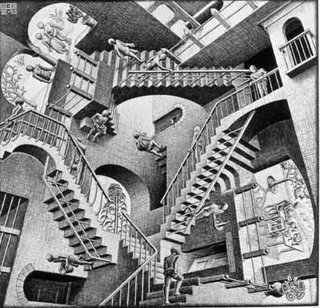

sophical practice, I am an anti-foundationalist, believing that there is no ultimate ground, that there is no secure foundation for [representational] truth, and emphasizing the emergence of universes of reference (of course, I make exceptions for the Lacanian real, truth in Badiou's sense, and mathematics). There is thus a great schizophrenia between my teaching and my writing. And indeed, it could be asked, whether my teaching isn't really my truth or my genuine conviction. As Zizek argues, the symbolic isn't premised on my personal belief in it, but rather, the efficacy of the symbolic is premised on my belief that others believe in it. I don't mow my lawn because I believe it's important to mow my lawn, but rather I mow my lawn because I believe my neighbors believe that it is important to mow the lawn. Thus, if I am a defender of reason, forms, foundations, grounds, and truths in the classroom, understanding my own practice as that of being a sophist in relation to my students so as to awaken them from their relativistic slumbers and critically think through these things, isn't this conception of myself as a sophist cynically propogating the myth that there is rational truth itself just a fantasy that allows me to avoid confronting the traumatic truth about myself, that it is I who really believes these things or hold these convictions? Isn't this the trauma that I experienced in the United States after 9-11 as I watched the nation so easily succumb to the most elementary ideological tricks described by George Orwell in 1984, believing that this was impossible after the WWII era, yet seeing it unfold right before my eyes, horrified to discover that persuasion and reason somehow do not really work, that we are not rational creatures? Yet my thought process here is muddled. The more accurate thematization of my transference with regard to my students would be that it is I who am the genuine nihilist and relativist, and that in a desparate attempt to deal with the directionlessness of my lack of conviction, I instead project this Nietzscheanism on to them so that I might persuade them, all the while persuading myself, that there is some truth independent of their will, perception, or subjectivity. The old-school Freudians, no doubt, would diagnose this as a megalomaniac fantasy, or the unconscious desire to create the world oneself by possessing sovereign power over the creation of truth. Nietzsche says something not dissimilar in his analysis of the will to power, behind the will to truth, where he points to the way in which the philosopher, in his ressentiment, elides the performative dimension of his discourse.This will to power aside, I cannot cure myself of the allegory of the cave, or of the conviction that philosophy should mark a journey from deceptive appearances to true reality, and it is this that always plagues me. I continuously oscillate between my constru

ctivism, my perspectivism, and the conviction that philosophy ceases to be philosophy the moment it claims all is simulacra, all is perspectives, all is appearances. I cannot escape my Enlightenment desire for a truth that can be discovered if we only break from appearances (including in terms of sensation), ideology, and superstition. But having learned the lessons of folk such as Derrida, Deleuze, and Horkheimer and Adorno well, I come back around to the position that the critique of ideology and superstition themselves are premised on ideology and superstition, and that there is no view from nowhere. Yet the moment I endorse that thesis, all truth is devalued and there's no point in saying much of anything at all as one "truth" is just as good as another truth. It might appear promising to celebrate the infinite creations of desiring-machines or simply affirming this or that perspective without ground, but don't these affirmations themselves reinstitute a sort of reflexive paradox by instituting a distinction between appearance and reality, where appearance has become the conviction that there is true-reality and reality has become the ascension out of the cave where one recognizes there are only anarchic desiring-machines or perspectives or language games or universes of reference or systems or whatever term one might wish to use? That is, isn't one playing the same game in inverted form and claiming to adopt a perspective outside of perspective where the only forbidden perspective is the perspective that there's a true perspective? And if such a position can be consistently affirmed, does not the discourse of philosophy become just one more flapping mouth, completely optional, with little or no critical force as there are no reliable grounds for persuasion? This, probably, is the heart of my sickness... The belief that persuasion is possible (doesn't persuasion always required that the person to be persuaded already believe what they are being persuaded of, thereby repeating Meno's Paradox, albeit in a different form, such that the reason I came to believe Lacan says something true isn't because Lacan gave me good reasons leading to his conclusions-- indeed, I could hardly make heads or tails of what he was saying --but because I already attributed truth to Lacan, and similarly with Badiou, Hegel, Deleuze, Luhmann, etc). Perhaps I would do better to believe in seduction, contamination, the viral, the secret agent.

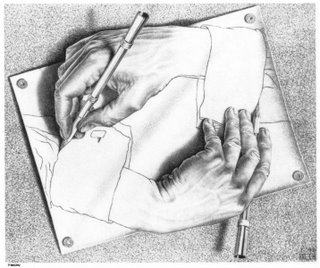

ctivism, my perspectivism, and the conviction that philosophy ceases to be philosophy the moment it claims all is simulacra, all is perspectives, all is appearances. I cannot escape my Enlightenment desire for a truth that can be discovered if we only break from appearances (including in terms of sensation), ideology, and superstition. But having learned the lessons of folk such as Derrida, Deleuze, and Horkheimer and Adorno well, I come back around to the position that the critique of ideology and superstition themselves are premised on ideology and superstition, and that there is no view from nowhere. Yet the moment I endorse that thesis, all truth is devalued and there's no point in saying much of anything at all as one "truth" is just as good as another truth. It might appear promising to celebrate the infinite creations of desiring-machines or simply affirming this or that perspective without ground, but don't these affirmations themselves reinstitute a sort of reflexive paradox by instituting a distinction between appearance and reality, where appearance has become the conviction that there is true-reality and reality has become the ascension out of the cave where one recognizes there are only anarchic desiring-machines or perspectives or language games or universes of reference or systems or whatever term one might wish to use? That is, isn't one playing the same game in inverted form and claiming to adopt a perspective outside of perspective where the only forbidden perspective is the perspective that there's a true perspective? And if such a position can be consistently affirmed, does not the discourse of philosophy become just one more flapping mouth, completely optional, with little or no critical force as there are no reliable grounds for persuasion? This, probably, is the heart of my sickness... The belief that persuasion is possible (doesn't persuasion always required that the person to be persuaded already believe what they are being persuaded of, thereby repeating Meno's Paradox, albeit in a different form, such that the reason I came to believe Lacan says something true isn't because Lacan gave me good reasons leading to his conclusions-- indeed, I could hardly make heads or tails of what he was saying --but because I already attributed truth to Lacan, and similarly with Badiou, Hegel, Deleuze, Luhmann, etc). Perhaps I would do better to believe in seduction, contamination, the viral, the secret agent.And so I start all over again like a fly trapped in a bottle, trying to draw my hands drawing themselves. I start developing the resources of critique, of analyzing the mechanisms by which power and persuasion

function, by theorizing what might be beyond superstition and ideology, and so on, only to find myself in the position so well described by Sloterdijk:

function, by theorizing what might be beyond superstition and ideology, and so on, only to find myself in the position so well described by Sloterdijk:Cynicism is enlightened false consciousness. It is that modernized, unhappy consciousness, on which enlightenment has labored both successfully and unsuccessfully. It has learned its lessons in enlightenment, but it has not, and probably was not able to, put them into practice. Well-off and miserable at the same time, this consciousness no longer feels affected by any critique of ideology; its falseness is already reflexively buffered.That is, I find myself in a position where I suspect that there must be a trick behind every claim or assertion, a hidden metaphysical presupposition, a hidden ideological assumption, a hidden class privilege or perspective, an unconscious desire quite unrelated to what I'm working on but nonetheless delivering me a certain jouissance in a subterranian and distorted form, and so on. The great masters of suspicion, Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud, all showed how there's a rational kernal behind the irrational in distorted form (well perhaps not Nietzsche, but certainly Freud and Marx), yet in doing so they also seemed to plunge us into a hall of mirrors facing one another, where there is no longer any firm ground upon which to set ourselves, undermining the idea of critique altogether in the long run. And so I fly about, hitting the walls of my bottle, never finding the way out. I tell myself that one must simply choose and proceed from there, yet I even find reasons to suspect such choices. I thus endlessly find myself plagued with the threefold question: What is philosophy? Where does one begin in philosophy? And what is the point of philosophy? I don't have the answer to these questions and perhaps all of this is simply an obsessional symptom to ensure that the practice of philosophy, which never has a proper beginning, should forever be deferred. I should listen more carefully to Socrates, with his doctrine that philosophy always begins with a random encounter. I should listen more closely to Hegel, with his position that the aim of philosophy, along with the knowledge of what philosophy is, always comes at the end. But I find myself unable to shake the desire to know at the beginning. Anyone have an antacid?

9 Comments:

The limit of philosophy comes with its own concept. All words are limited by its concepts, ¿given by us, society or by the dictionary? Although dictionary definitions may vary from each individuals true use, we tend to see how art can unveil this.

Those society or self imposed limits can be crossed, and at that instant we will be different.

–It could be called evolution.–

If you think something today, crossing your own limits will transform you into being more conscious about the things that surrounds us.

If we take this as a common understanding we are limited by our thoughts. That is we can only live and be what we think we are. We live in paradigms that could be crossed, but our fear maintains us in the same concept.

The only way to cross concepts, and understand existence is to go to those concepts spend time doubting their definitions, and then come up with our own definitions. Then, at least we will individually understand what really is:

Philosophy?

Love?

Fear?

Limits?

Fulfillment?

Why do I use these words? It is a fact that as humans beings we cannot leave love and fear out of the equation. Those are basic words for understanding ourselves. If we cannot see how fear limits us, then we could be trapped in a way of seeing life that is not helping us as human beings to evolve.

The universe is interrelated, and constantly evolving. We cannot leave a piece apart because it all comes together. The moment we choose to see just one point of the whole concept soup: The world is flat and gigantic turtles hold it for us.

We are living times that are shouting for unity, like cognitive sciences, and other disciplines of knowledge that are uniting to really give sense complete to our concepts.

How can we cross our limits? What is the use of evolution if there is no peace of mind, no love, no fulfillment? Where do we choose to go? The question seems easy, but is the answer?

as an antacid, or maybe just for more feasting, I advise Werner Hamacher’s Pleroma.

Levi, this is a moving as well as a seminal post. Thanks so much for sharing it.

It provokes all sorts of reactions.

First off, I think you might make a distinction between the professional and the private philosopher. As a teacher you are a modern day sophist selling your knowledge - which is an admirable enterprise benefitting your students who will acquire analytical tools making them able to debunk a lot of the white noise and hype of communication surrounding them.

As a private philosopher you are occasionally infected by the virus of Kierkegaardian angst and/or cynicism. You are not alone. But you do not suffer from a ”sickness” as you write. Maybe it is more a case of self-persuasion (cf. your eloquent explanation of being already persuaded before you realize it.)

Yes, we believe in the power of persuasion, but hey, Socrates had it easy. Most people who came to him always left persuaded – and even thankful.

Another thing: Aren’t you turning philosophy into teleology – with a heavy Hegelian heart. Lighten up – with a Nietzschean walk in the mountains.

When you can bring so much intellectual joy, not only to your students, but also to us your grateful readers, doesn’t that make philosophy worth your while?

I just looked up the definition of a philosopher from the Enlightenment bible: Diderot’s and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie,1765. (Your French is better than mine I know, but I translated a few passages all the same:

Other people are destined to neither feel nor recognize the causes that move them, without even thinking about what the causes are. The philosopher, however, untangles them as well as he can and sometimes even knows them beforehand and then surrenders himself to them knowingly.

The philosopher is, as it were, a clock that sometimes has to wind itself up.

Thus he avoids things that produce feelings which are neither suitable to his well-being nor to a man of reason. Instead he always seeks out situations that create sentiments applicable to the condition he is in…

Other people are at the mercy of their passions without first having thought about their actions. They are people moving in the dark, whereas the philosopher, even in the midst of his passions, does not act before having thought.

He walks in the night but there is a torch in front..

Get well, soon, Levi. On the other hand, when you produce essays like this in “despair”, you don’t NEED to get healthy ;-))

PS: I really appreciate your pictures. And I thank you for mentioning and quoting Peter Sloterdijk. He is a welcomed modern German voice of sanity and a stylistic magician. Let’s return to him soon.

Orla Schantz

I've always been an incurable relativist nihilist but I whenever I see a movie of Black Hawk Down's variety, I still can't help but admire all those poor bastards who really seem to believe that they are doing the right thing.

Lina, Thanks for the comments. I'm sympathetic to a number of the claims you make (although I don't endorse ontological holism). However, for me the one aspect of being that always stands in stark contrast to evolution or constant becoming is mathematics. While it's certainly true that math is always advancing its boundaries, I take it that mathematical truths once discovered are always true (i.e., they don't become "extinct"). Even more remarkably, the world itself is mathematical (I'd be shocked to discover that a convention such as the game of chess can also be found naturally occuring). If there are mathematical truths, that have these characteristics of being eternal, universal, etc., then why not others?

s0m3times, Thanks for the reference. Hegel is a constant flirtation for me. While I'm not so keen on most of his work, I've never quite been able to shake myself of the Logic. Lenin claimed that one must read Hegel's Logic to understand Marx, so I suppose I'm in good company.

Great quote, Orla! I wish my german were better, I'm dying to read Sloterdijk's Spheres. Have you looked at it?

Burham, if you haven't looked into him already you might enjoy Badiou. He strikes me as doing something very different than the standard postmodernism (and it's Anglo-American variants) and Globalization raps. Even if Badiou's project ultimately fails, it will be a worthwhile failure in pushing discourse in a different direction and resuscitating the notion of truth as central to philosophy.

Thank you for these words and the honesty with which they are delivered.

"Sometimes a cigar is..." Right?

What is philosophy? Living.

Where does one begin in philosophy? With the desires which draws us into life.

And what is the point of philosophy? As defined, there is no need for an answer here.

I mean, I suppose that I'm putting forth some sort of critical realism where the real sends us searching for the language adequate to its expression, but language is, of course, conditioned, ephemeral. Don't you need to look at the polis? You do live somewhere. You do feel the desire to eat. Racoon-marriage issue aside, you do share something with animals in these impulses, which gets you beyond the human.

Though I started with stark answers, I, of course, don't have them.

Post a Comment

<< Home