From Multiplicity to Unity: The Problem of Differential Ontology

Following Nick's suggestion over at The Accursed Share, I've been working my way through Alberto Toscano's The Theatre of Production: Philosophy and Individuation Between Kant and Deleuze. Although outrageously priced at $74.95 (what's with Palgrave?), this book will definitely be of interest to anyone interested in differential ontology and why the question of individuation plays a central role in the thought of Simondon and Deleuze. Not only does Toscano present a brilliant and informed archaeology of how this problem emerges out of the discussion of biolife in Kant's Critique of Judgment, where biophysical organization cannot be comprehended in terms of the categories of the understanding and thereby falls outside of transcendental constitution by mind, and how thinkers such as Nietzsche sought to give an account of organized systems that avoided the shortcomings of both theologically driven teleological approaches and mechanism, but it also presents a substantial discussion of Deleuze's ontology of problems and actualization.

Following Nick's suggestion over at The Accursed Share, I've been working my way through Alberto Toscano's The Theatre of Production: Philosophy and Individuation Between Kant and Deleuze. Although outrageously priced at $74.95 (what's with Palgrave?), this book will definitely be of interest to anyone interested in differential ontology and why the question of individuation plays a central role in the thought of Simondon and Deleuze. Not only does Toscano present a brilliant and informed archaeology of how this problem emerges out of the discussion of biolife in Kant's Critique of Judgment, where biophysical organization cannot be comprehended in terms of the categories of the understanding and thereby falls outside of transcendental constitution by mind, and how thinkers such as Nietzsche sought to give an account of organized systems that avoided the shortcomings of both theologically driven teleological approaches and mechanism, but it also presents a substantial discussion of Deleuze's ontology of problems and actualization.In the first meditation of his Being and Event, Badiou writes that,

Since its Parmenidean organization, ontology has built the portico of its ruined temple out of the following experience: what presents itself is essentially multiple; what presents itself is essentially one. The reciprocity of the one and being is certainly the inaugural axiom of philosophy-- Leibniz's formulation is excellent; 'What is not a being is not a being'-- yet it is also its impasse; an impasse in which the revolving door of Plato's Parmenides introduces us to the singular joy of never seeing the moment of conclusion arrive. For if being is one, then one must posit that what is not one, the multiple, is not. But this is unacceptable for thought, because what is presented is multiple and one cannot see how there could be an access to being outside all presentation. If presentation is not, does it still make sense to designate what presents (itself) as being? On the other hand, if presentation is, then the multiple necessarily is. It follows that being is no longer reciprocal with the one and thus it is no longer necessary to consider as one what presents itself, inasmuch as it is. This conclusion is equally unacceptable to thought because presentation is only this multiple inasmuch as what it presents can be counted as one; and so on. (23)From a certain vantage the entire history of ontology can be read from the standpoint of this aporia. Badiou's thesis here-- and it is a thesis shared by Deleuze in Difference and Repetition --is that the suture of being to the one, the reciprocity of being and the one, leads to irresolvable antinomies for thought. If we treat being as one, then the multiplicity of beings characterizing presentation disappear. If we treat being as multiplicity, then it seems that all beings disappear. It is thus not a preference, or moral and political inclination, that drives Deleuze and Badiou to think being as multiplicity without one-- though certainly such an ontology will have profound moral and political implications --but an attempt to think through this impasse of thought, this aporia, by severing the suture of being to the one.

In this regard, both Deleuze and Badiou will be united in arguing that the unity of a being is a result, product, or effect, rather than an ontologically primitive feature of being. The unity of a being is a result, an emergence, rather than an essential feature of being. Toscano expresses this point beautifully in relation to Nietzsche-Lange's thesis that all unity is relative.

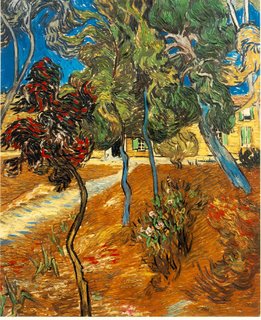

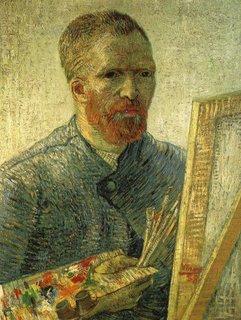

...the relativization of unity predicated upon the farewell given to that 'favorite idea', self-consciousness, makes the infinite proliferation of multiplicity, its availability as the material upon which the intellect carves its relative unities, into the precondition for unity itself. Within what nevertheless remains a very tentative consideration of the question of the One and the Multiple, based on the naturalization of the critical project and the confrontation with the paradoxes of the Will, we could summarize the stance proposed by Lange and the early Nietzsche in the following dictum: a multiplicity is a unity for another multiplicity. Or, returning to the theme of the anomaly of the organic: a multiplicity is an individual for another multiplicity. (Toscano, 96-7)As a result of this thesis we are faced with the question of how a multiplicity can become a unity for another multiplicity, or how a multiplicity can become an individual for another multiplicity. Like an impressionist work of art or painting by Van Gogh, the unity constituting the whole is only an effect of a multiplicity of pulsating differences that can themselves be taken as unities in their turn, abolishing the unity of the painting as a totality. In Luhmannian terms, this question will be that of how a system constitutes its own elements from chaos (Luhmann's term for "inconsistent multiplicity"). Similarly, Deleuze, in Empiricism and Subjectivity, will remark that,

The mind is not nature, nor does it have a nature. It is identical with the ideas in the mind. Ideas are given, as given; they are experience. The mind, on the other hand, is given as a collection of ideas and not as a system. It follows that our earlier question can be expressed as follows: how does a collection become a system? The collection of ideas is called "imagination," insofar as the collection designates not a faculty but rather an assemblage of things, in the most vague sense of the term: things are as they appear-- a collection without an album, a play without a stage, a flux of perceptions... The place is not different from what takes place in it: the representation does not take place in a subject. Then again the question may be: how does the mind become a subject? (22-3)Indeed, if we follow Badiou's account of multiplicity, then the situation is even worse than what is here described by Deleuze, for what constitutes being qua multiplicity cannot even be said to be a collection as

the concept of a collection already implies an operation of unification. Moreover, as Toscano later notes, we cannot even ascribe this operation to mental operations such as those carried out by the understanding (early Nietzsche's provisional solution), as the understanding must itself result from such a process of individuation (Toscano, 105; it will be recalled that Deleuze calls for a genetic account of the faculties in Nietzsche and Philosophy, arguing that Kantian critique is insufficient as it doesn't account for the individuation or genesis of these faculties themselves. This opens the door to a naturalist or post-Darwinistic account of cognition). If we were to argue that these unities wherein a multiplicity is constituted as an individual for another multiplicity are constituted through the work of the understanding, then we would necessarily be forced to claim that mind is outside of being or something other than being, thereby undermining the thesis of immanence (that being is immanent to itself) and reintroduce both transcendence and dualism. Consequently, a cognitive account of individuation will necessarily prove insufficient as it is premised on the thesis that individuation has already taken place; which is to say, it presupposes that the faculties by which other multiplicities might be individuated have themselves already been individuated. What is required is thus an ontological account of individuation.

the concept of a collection already implies an operation of unification. Moreover, as Toscano later notes, we cannot even ascribe this operation to mental operations such as those carried out by the understanding (early Nietzsche's provisional solution), as the understanding must itself result from such a process of individuation (Toscano, 105; it will be recalled that Deleuze calls for a genetic account of the faculties in Nietzsche and Philosophy, arguing that Kantian critique is insufficient as it doesn't account for the individuation or genesis of these faculties themselves. This opens the door to a naturalist or post-Darwinistic account of cognition). If we were to argue that these unities wherein a multiplicity is constituted as an individual for another multiplicity are constituted through the work of the understanding, then we would necessarily be forced to claim that mind is outside of being or something other than being, thereby undermining the thesis of immanence (that being is immanent to itself) and reintroduce both transcendence and dualism. Consequently, a cognitive account of individuation will necessarily prove insufficient as it is premised on the thesis that individuation has already taken place; which is to say, it presupposes that the faculties by which other multiplicities might be individuated have themselves already been individuated. What is required is thus an ontological account of individuation.A good deal of Toscano's solution to this problem seems to revolve around habit, as that force that binds multiplicities together giving rise to emergent and enduring systems or unities. "...[F]ar from consisting of a modification that happens to an individual, which would then endure like a substantial kernel of permanence beneath the more or less adventitious effects of habit, beings are indeed nothing but relatively stable 'bundles of habits'" (122). Under Toscano's account we do not first have individuals that are then capable of producing habits, but rather, individuals themselves result from habit or the syntheses effected by habit. We must take great care here lest we think of habit as merely a psychological principle. Within the scope of Toscano's proposal (which he shares with Deleuze, James, and Peirce), habit is a genuinely metaphysical principle presiding over the emergence of any individual whatsoever. Rocks are habits, trees are habits, the sun is a habit, etc. As Deleuze so poetically puts it,

We are made of contracted water, earth, light and air-- not merely prior to the recognition or representation of these, but prior to their being sensed. Every organism, in its receptive and perceptual elements, but also in its viscera, is a sum of contractions, of retentions and expectations. (Difference and Repetition, 23)And

No one has shown better than Samuel Butler that there is no continuity apart from that of habit, and that we have no other continuities apart from those of our thousands of component habits, which form within us so many superstitious and contemplative selves, so many claimants and satisfactions: 'for even the corn in the field grows upon a superstitious basis as to its own existence, and only turns the earth and moisture inIn passages such as these it is clear that Deleuze conceives habit as a genuinely materialistic principle, rather than simply a mental principle. To my thinking, Deleuze here shows an advantage over Badiou, for Badiou 1) gives no real account of how the operation of the count-as-one comes to operate (what is the operator of the count-as-one?), and 2) tends to assimilate the operation of the count-as-one to operations operated by social systems and linguistic operations, thereby implicitly refusing any individuating operations to being as it operates independent of human beings. Moreover, the advantage of an account of individuation based on habit is here patent, as it allows us to account for the emergence of order or organization that preserves the creative nature of being and that requires no recourse to pre-established forms, laws, or essences. Hence Toscano will propose that we refer to this account with the beatiful title "anomalous individuation" (he seems to have a knack for such coinages, proferring terms like "aleatory rationalism", and "transcendental materialism", as well), thereby capturing the manner in which the individuated individual emerges as a solution to a problem defined by a unique situation.to wheat through the conceit of its own ability to do so, without which faith it were powerless...'. Only an empiricist can happily risk such formulae. What we call wheat is a contraction of the earth and humidity, and this contraction is both a contemplation and the auto-satisfaction of that contemplation. By its existence alone, the lily of the field sings the glory of the heavens, the goddesses and gods-- in other words, the elements that it contemplates in contracting. What organism is not made of elements and cases of repetition, of contemplated and contracted water, nitrogen, carbon, chlorides and sulphates, thereby intertwining all the habits of which it is composed? (75)

The difficulty I have with Toscano's solution is that it seems to undermine the initial ontological thesis that the one is not. If we recall Deleuze's account of habitus, repetition changes nothing in the thing repeated, but it does change something in the mind that contemplates this repetition. Clearly we're going to have to erase all reference to mind if we want this to be a genuinely materialist account of individuation; however, this is not the problem. Rather, the problem lies in the assertion of a repeating thing. That is, all things being equal, the thing that repeats must necessarily itself be a result of a process of individuation. But the principle of habit is designed to account for how something is individuated at all. The problem is that we must presuppose an always-already individuated result (the repeating element) to account for how another multiplicity can grasp this repeating element to bind it and individuate a new being. But if this is the case, we've undermined our initial thesis that being is pure multiplicity. While we can certainly hedge and say that individuation is always-already up and running-- "that we always begin midstream" --this leads one to wonder why we would then assert that being is multiplicity without one at all. There's something missing here and I'm having difficulty putting my finger on it.

2 Comments:

As usual, another excellent post mapping out relations between Deleuze and Badiou. I'm not sure how you are so prolific with your writing, but I for one, am impressed!

On the issue of your last paragraph and the difficulties outlined there, I wonder whether or not Toscano's discussion of spatiotemporal dynamisms in section 6.3 (p. 175-180) might not have some relevance? I find those pages incredibly dense, but the glimmers of understanding I get every now and then seem to pertain to the concern you raise. In particular, it seems as though there's a movement away from habit as the principle guiding actualization, to an idea of dramatization as the nature of individuation. While it doesn't explicitly resolve the problem of moving from multiplicity to unity, I think it opens up a new way to think the process involved.

Nick, I haven't gotten that far yet (I'm just starting the chapter on Simondon), so I'll look forward to that material. I suspect that part of the problem is that I'm conceiving multiplicities too much in Badiou's terms as infinitely disseminating sets without final or ultimate terms. Badiou's multiplicities, by contrast, are differential networks. The idea of recursive evolution that Toscano discusses in the chapter on Peirce seems to go some of the way towards addressing this question, as we perpetually have new actualizations emerging out of current actualizations as what evolves generates new problematic fields calling for further developments. Conceiving multiplicities as differential networks preserves an ontology of difference in that a differential (dy/dx) marks a rate of change or differences, while also promising an explanation of how one multiplicity can take another multiplicity as an individual, as the differentials precipitate singularities that preside over genesis... Or something like that.

Post a Comment

<< Home